We believe building Danish-style cohousing in San Francisco is a solution that addresses both this recent social disconnect and San Francisco's lack of affordable housing for working-class residents and families.

Today, about 7% of the Danish population live in cohousing, coliving, or co-operatively owned housing, accounting for one-third of Copenhagen's housing stock.

Berkeley, Emeryville, Oakland, and folks in other Bay Area cities have built thriving cohousing housing communities over the last few decades. However, San Francisco completely lacks cohousing options for residents. We believe cohousing should be an available housing option in San Francisco.

Imagine a home...

Where you you live near friends in a community.

A community with individual homes as well as communal spaces such as a communal dining area, workshops, garden spaces, and more.

Housing that provides the right balance between privacy and community.

Imagine all of the ways this could change your life…

Weekly communal dinners and time well spent with friends.

Conversations and connections with the people you love.

Quality time with your kids and fewer hours spent on screens.

Access to an art studio, gym, spaces for children, and more…

What can be built in SF?

Different neighborhoods in SF can support different size projects

Neighborhoods with large empty offices, factories, and lots like the Dogpatch could fit a larger project.

Neighborhoods with medium-sized empty retail and office buildings like Hayes Valley could fit a medium project.

Neighborhoods with smaller-scale buildings like Noe Valley could fit a smaller project.

Who is organizing this project?

We are a team of architects, housing experts, and cohousing enthusiasts who want to see change happen in San Francisco.

Our goal is to see cohousing built in San Francisco. Cohousing is the English word for the Danish concept of bofællesskaber, which translates to “living community.”

Our advisor is architect Charles Durrett. Durrett has designed and help build over 55 bofællesskab-style communities in North America, including the first community in Davis, California, in 1989, and has consulted on many more around the world.

What is a Danish bofællesskab-style community?

Other names you might have heard before are “friend neighborhood,” “Cohousing,” “Clustered housing,” "Minihood,” or “Pocket neighborhood.”

Bofællesskab-style communities are most often called cohousing in the United States. However, cohousing is not “coliving” or “shared housing”.

Every home is an individually owned private home—with a full kitchen, its own bathrooms, and everything else you would expect in a standard home. Cohousing allows you to have the right balance between as much privacy and as much community as you want.

Cohousing is very much like any other cluster development with a homeowners association, except cohousing communities are designed and owned by the people who will live there. The master plan and common areas are designed so that people know, care for, and support their neighbors. This approach originated in Denmark and is popular across Europe.

Everyone has their own home and privacy, but there is also a central community space where residents share meals, bake bread together, have childcare on-site, and participate in innumerable other activities. Individuals own their own home and as a community you own the communal areas under an LLC.

Charles Durrett, introduced the concept of cohousing to the United States with the seminal book Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves. He has helped groups of friends build Danish bofællesskab-style neighborhoods dozens of times over the last 30 years.

This approach to neighborhood design originated in Denmark and is popular across Europe. Durrett was the first architect from America to study how to design and build bofællesskab-style housing under the people who invented this type of community-enhanced design in Denmark.

He is an authoritative expert on building these mini-neighborhoods. He has spoken before the United States Congress multiple times. His work has been featured in Time Magazine, The New York Times, The LA Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Architecture, Architectural Record, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, and many more.

There are many good architects who can design communities that look like cohousing on the surface, but the real challenge is building the community. An architect needs to guide the group into making the right design decisions that will allow and encourage individuals to benefit from time spent together in communal spaces. An architect trained in designing cohousing does this through a participatory design process. In practice, this takes the form of you and other future residents participating in fun and interactive design workshops that bring out your group's best ideas and align you on critical decisions.

The skill needed to make this process fun, efficient, and effective is unique to a skilled cohousing architect. A typical architect likely wouldn't even consider trying to work with a large group of friends, let alone be able to navigate the process in an efficient and skilled way that would result in an outcome the group was happy with.

This results in not only a much more committed and invested homeowner but also a tight-knit community where people trust, support, and care about one another well before the housing is built.

Durrett learned how to facilitate groups and design cohousing from the best of the best in the world — from both the person who started it, Jan Gudman-Høyer, and the person who perfected it, Àngels Colom—as well he studied under Jan Gehl. Years later, things came full circle when many of the current set of leading Danish cohousing architects studied in California under Durrett.

Durrett has previously won the “Best In American Living Award—Best Community” from NAHB in a year when ~1.6 million homes were built in the U.S., the “World Habitat Award” from the UN, and dozens of other awards for his cohousing community designs.

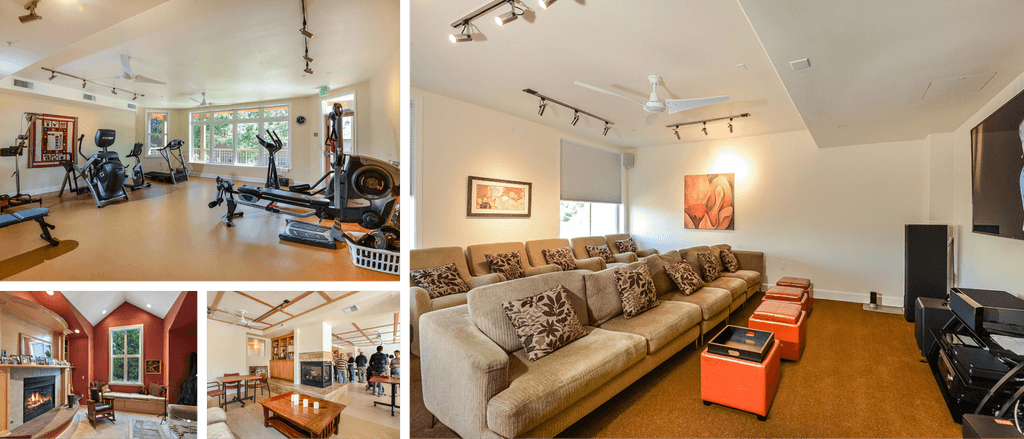

What kind of communal spaces are possible?

Example spaces from past projects include art studios, a resident café, a library, a bike workshop, a maker space, guest rooms for visiting family and friends, and gyms — what you build depends on what you decide as a group matters to you!

A communal garden, a bike workshop, a dance hall, and a wood working workshop.

These examples are from previous projects by Charles Durrett.

Additional examples: a gym, fireplace room, communal hang out areas, and a theatre room

Examples of spaces for children and childcare

Examples of outdoor spaces for children and families. Nevada City Cohousing, Nevada City, CA.

Amenities from Treehouse Community: rooftop deck, Resident Café, Lounge, Library, and a Recording Studio.

Treehouse Community is a coliving apartment in LA, that Charles Durrett consulted on.

The importance of the “Common House”

With cohousing elements that enhance and enable social activity, and serendipity are of the highest priority. Without these elements a cohousing community will be little more than a traditional residential condo development.

Everyone has their own home and privacy, but there is also a central community space, called a “Common House”, where residents share meals, bake bread together, have childcare on-site, and innumerable other activities. Hearthstone Cohousing, Denver, CO; MVCC, Mountian View, CA; Silver Sage Village, Boulder, CO;

In fact, the success of a cohousing community depends upon the “common” realm — the places where residents come together for socializing, creating, or just saying hello. These everyday acts are what keep residents connected. When buildings are scattered across a landscape, the Common House gets very little use and the sense of community is diluted.

Every cohousing community needs a central node or plaza that offers people opportunities for seeing or being seen. Like an old town square, it provides space for larger gatherings and enables people to come together, designed with active edges that encourage people to congregate, sit, observe, and interact.

The Common House is the heart of the community, so its design is very important to facilitating social interaction and the workings of the community. Because the Common House is the physical and the communal anchor of the community we take its planning very seriously. It is the link between home and neighborhood. Acoustics, lighting, accessibility, presence of other common areas (a kid’s room and yoga room, for instance) are all considerations of great importance when designing a Common House. This is why having an experienced architect and/or acoustical engineer, experts who have successfully created common areas that are welcoming and not institutional, is very important. The difference between a well-programmed, well-designed Common House and one that is not done with adequate feedback from the group can be a difference of hundreds if not thousands of people hours spent or not spent in the Common House.

Breaking bread together is timeless. In a high-functioning cohousing, residents talk of common meals as the highlight of their cohousing experience. Without the presence of a Common House, a community will struggle to fully experience the positive effects of having each other around.

Our philosophy

We started this project because we believe the current philosophy around housing needs to be challenged. San Francisco needs real solutions that will benefit people from all income levels, ages, backgrounds, and circumstances. We need solutions that serve the people who will be living in the future houses that will be built. Not solutions that help large national real estate developers just build more of what has been built for the past 80 years.

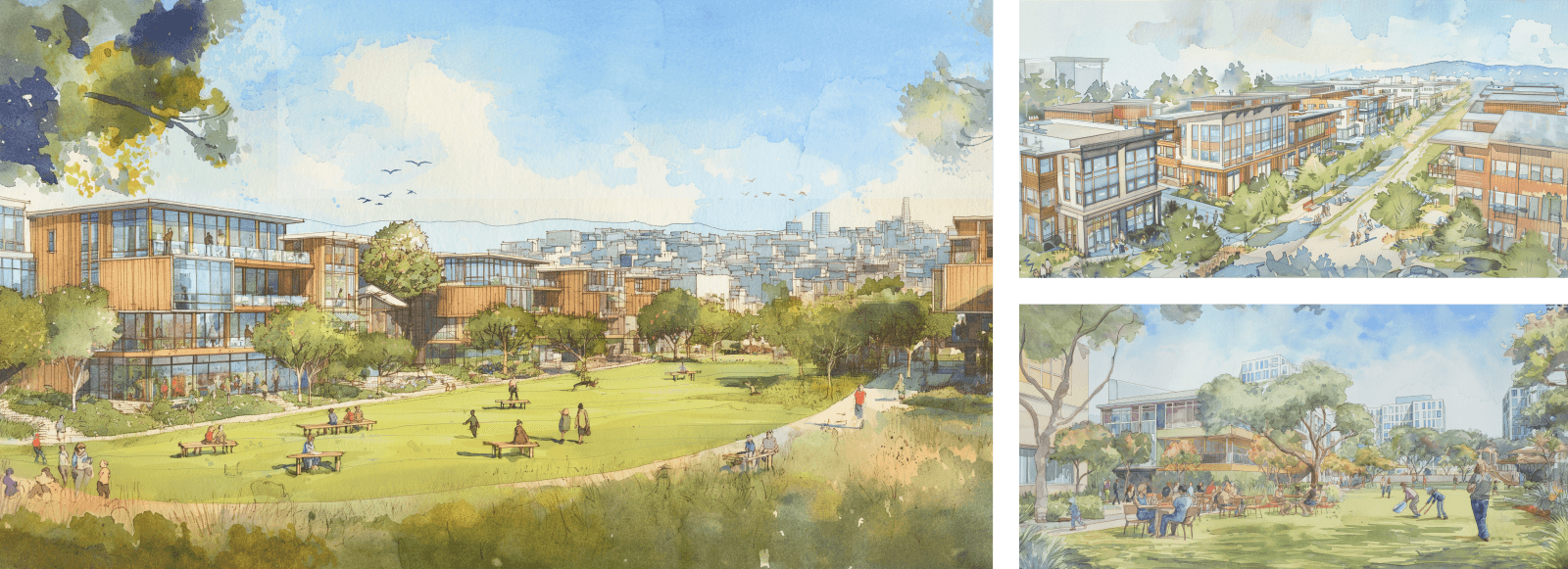

Concept — a village in the Dogpatch

We believe the housing crisis and loneliness epidemic across America have gone on for too long. Immediate action is needed and it’s time to build and improve the already existing high-functioning, walkable neighborhoods that form authentic communities of San Francisco.

We believe every neighborhood in San Francisco should strive to have multiple cohousing communities—where connection and serendipity are designed to happen for people of all ages (from seniors to children and families) and from all backgrounds.

Why does the design of where you live matter so much?

Did you know the number one predictor of happiness in life is the number of close friends you regularly see?

“Close relationships, more than money or fame, are what keep people happy throughout their lives, the study revealed. Those ties protect people from life’s discontents, help to delay mental and physical decline, and are better predictors of long and happy lives than social class, IQ, or even genes. That finding proved true across the board among both the Harvard men and the inner-city participants.”

— Source: The Harvard Grant Study, the longest running study of its kind.

However, you would be hard-pressed to design a more effective system than today’s city and suburb design to choke the joy out of life and prevent people from spending quality time with friends.

We've grown so acclimated to the tyranny of car-centric neighborhoods and exclusionary zoning that we have become blind to its insanity.

In contrast, if you live in a neighborhood where you can walk less than 10 minutes to the grocery store, to drop your kids off at school, to shopping, to your best friend's house for a BBQ—you won’t ever want to spend 97 hours a year in traffic again.

However, cohousing is not anti-car. Cars play an important role in cities like SF. Cars support traveling across town, visiting destinations outside of SF, visiting family in other cities, or for some people for their daily commute to work. But the more people we can get off the roads for daily trips that should be in their neighborhood, the less traffic we create for everyone.

The time we spend in traffic truly squeezes the life out of our day. For many people the few hours of leisure time we have are spent sitting in a car.

Moreover, the serendipity of running into friends is lost. Making plans is an ordeal compared to a regular occurrence that just happens at the local coffee shop. The reason so many people enjoyed their college experience is that for the first time in their lives, they lived in a walkable neighborhood where they could run into friends and make many of their trips without a car.

However, in North America, often only the wealthy can live like this because cities have made it illegal to build new mixed-use walkable neighborhoods with gentle density (duplexes, triplexes, and 2-3 story condos) that provides the density of people needed in a neighborhood to support local shops and services.

This makes these neighborhoods (designed before the invention of the car) both rare and highly desirable (expensive).

Types of cohousing projects

Cohousing projects can come in a wide variety of types. Learn about different size and types of projects below.

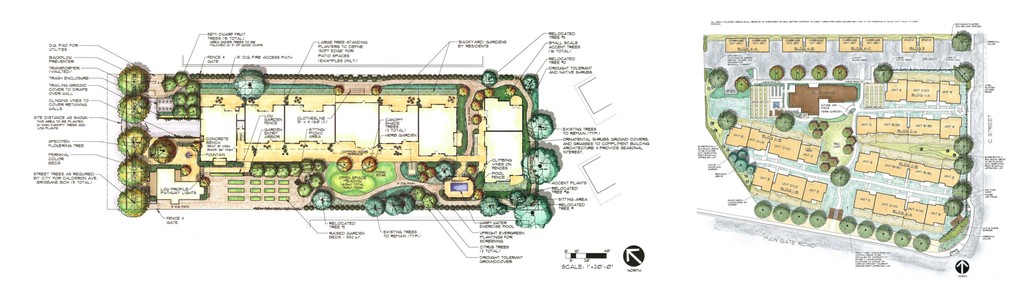

01. Suburban developments

Cohousing as an anchor for a larger suburb neighborhood

A cohousing community can be a great anchor for a larger suburb neighborhood. Hearthstone Cohousing Community in the Highlands Garden Village in Denver is a great example.

Hearthstone Cohousing Community acted as the anchor for the Highlands Garden Village planned community in Denver, CO. Developing this 28-acres deteriorated urban environment came with a lot of risk. However, today it is one of Denver's most desirable areas.

The 28-acre site had been home to an abandoned amusement park that caused significant blight to the surrounding area. Building a mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly community in a deteriorated urban environment came with significant risk.

The cohousing community brought the entire neighborhood to life. Nearly every house, townhouse, and loft was sold, and most apartments were rented out before final construction. Which is not common for large projects. Today, it is one of Denver's most desirable areas.

At the time, many new urbanist architects were trying to create community through walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods where community happens. However, community can only happen when a site is designed with the people who will actually be living there and with people who want to form a community with each other.

The sequel to this project was the Holiday Neighborhood in North Boulder, a mixed neighborhood with affordable and market-rate homes. Silver Sage Cohousing acted as an anchor.

Hearthstone Cohousing Community in the Highlands Garden Village in Denver, CO.

How is Hearthstone Cohousing doing 20 years later?

Hearthstone Cohousing Community by the Numbers

33 households in 7 multifamily buildings

About 76 residents, including 16 children (up to high school age), 8 adult children, and 11 seniors

9 units occupied by original owners who moved in in 2001

5 common meals per month

What are residents most proud of?

“Our wonderful kids who can always find someone to play with”

Delicious and diverse shared meals attracting 30-50 residents and their guests.

Beautiful Common House with its gourmet, commercial kitchen and lovely indoor and outdoor dining areas. We reserve it for private parties, meetings, retreats, etc.

“Wake the Neighbors”– a musical group of residents who’ve gotten so good that they play for weddings and parties.

Gardens and landscaping — planted and lovingly maintained by residents.

“All the ways we help each other”. To name a few: babysitting & driving kids; providing meals & support when someone is sick; sharing tools, equipment, & artwork; watering gardens; caring for pets; sharing professional expertise.

02. Urban developments

Urban medium density examples of cohousing located in: Mountain View, USA; Vancouver, Canada; Stavanger, Norway

Medium-density cohousing

This is the ideal style of project for the Dogpatch, Hayes Valley, or another similarly dense neighborhood in San Francisco. This style of project can be achieved through an office or factory-to-residential conversion approach or through ground-up construction.

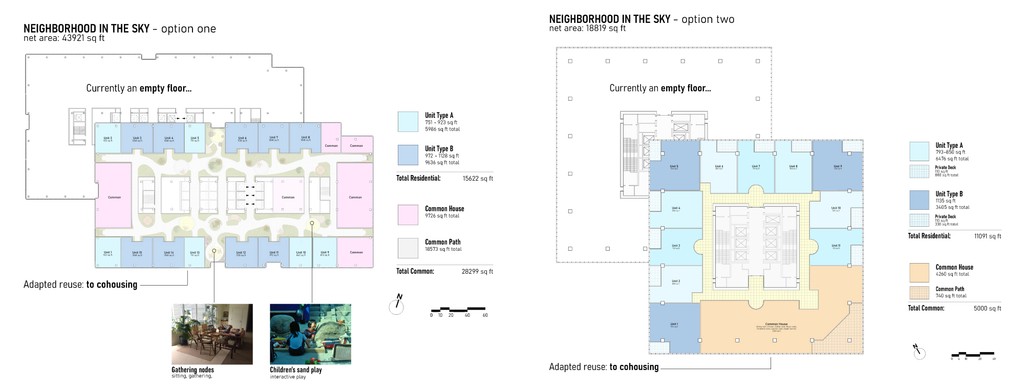

03. High-rise developments

Examples of high-rise cohousing in Sweden

A neighborhood in the sky

There is great potential in repurposing vacant office buildings in downtown areas with urban cohousing communities.

Reports vary that 26% to 33% of San Francisco’s high-rise square footage today falls below its highest and best use or stands empty. That’s a lot of the constructed world sitting empty. However, the big miss is that those empty or underutilized spaces could be converted into housing.

Sweden has been repurposing high-rises to housing since the 1980s. These neighborhoods in the sky work great for families and friends.

Conceptual floor plans for high-rise cohousing in downtown SF

Why is cohousing a better use for high-rises than typical condos?

Cohousing residents have their own private home (condo) with the addition of generous shared spaces and common amenities.

Redesigning these buildings to fit cohousing is easier than getting these high-rises to bend to any other use, because the shared common areas are a release valve for an otherwise difficult adaptive reuse project.

An example of a recent office-to-residential conversion near Hayes Valley

Office-to-residential conversions are possible for standard apartments and condos in the right building. However, buildings with large floor plates can be difficult to work with. Cohousing office-to-residential conversion allows for more building sizes and types to be converted.

The below video showcases a recent San Francisco office-to-residential conversion by a local real estate firm, Emerald Fund.

From 1974 to 2010, the high-rise at 100 Van Ness served as an office building and the longtime home to the California State Automobile Association (“AAA”). Over the course of 12 months, Emerald Fund removed the 1970’s era concrete panels, piece by piece, and replaced them with floor-to-ceiling glass. The short video captures the transformation of this San Francisco icon.

100 Van Ness office to residential conversion timelapse

What does a cohousing project's timeline look like?

Project steps

The process and timeline depend on the style of cohousing community your group wants to build. For building a mini-neighborhood in Hayes Valley (e.g. an office-to-residential conversion or ground-up new construction) let's look at the process below.

Step 1. Come to our talk on (date to be announced soon) to hear about the benefits of cohousing and more details of the process. Additionally, you can meet the people you may be designing and creating your community with.

Step 2. If there is enough interest among folks, we will organize a “get it built” workshop. This is a two-day workshop where we go into detail about the process of purchasing the land, obtaining the building permits, and constructing the buildings and homes. This is also the key step where the group forms, and some people may bow out as they realize this isn’t the neighborhood project or group for them. This self-selection is a useful part of the process.

Step 3. Over the course of 7 workshops over 12 days, the cohousing group will learn how to find and decide on land, or a building to buy. Then we will help you form an LLC and negotiate an option on your site while you get it entitled (permitted). You will work with Charles Durrett to design your homes and the larger community. We will involve you and the other future residents in interactive design workshops that bring people onto the same page in effective and fun ways.

This is the co-participation design process that makes cohousing unique. This process begins your journey of growing into a tight-knit community.

Step 4. We will help you submit your entitlement, permits, and other local requirements for approval. We will guide your group through the process of getting your project entitled by helping you learn how to either use existing land use law to your favor or advocate for discretionary review changes and/or zoning changes if needed.

Charles Durrett has a near impeccable track record for getting his projects entitled (securing permits and zoning adjustments). Out of the over 55 housing communities he has designed, all but one have been successfully entitled and permitted.

Step 5. With permits and plans in hand, we will help your group through the complex construction phase.

Step 6. It’s time to move in! You now own your custom home and share ownership of the common areas through the LLC you formed with your group.

Timeline

The group will move forward to the next step only if you want to. If, after the “get it built” workshop, you decide this isn’t a project for you, you can bow out at any time.

We will help the group negotiate land/building purchases that minimize the earnest money your group would need to put down. In some cases, you can negotiate no money down to tie up the property while you go through the entitlement process.

As a group we can decide how we want to approach entitlement. There is risk involved in this step; though the cohousing approach has a stellar record for getting projects entitled, ultimately, that doesn’t guarantee every future project will be entitled. Recently, many groups have been finishing initial plans and designs for their community before submitting them for permitting or a zoning change to show the board/council that this group of future residents is serious. There is risk in this approach as the group would have to spend some money (a few thousand dollars for each family) to create the plans. However, as a group, you can decide if you want to submit zoning changes (if you need them) before any drawings are created.

In recent years, many new laws have been written at the state level that actually help projects go through the planning meetings. Our team has experts in these new laws and regulations and can help you navigate some of the more complex options available to your group.

Who we are

Christopher Smeder

Cohousing Enthusiast & Group Coordination

Christopher is a co-instigator of this project. He and his wife Ashley have been dreaming about living in cohousing since well before their three-year-old son was born. They currently live in a one-bedroom rental near the Mission. However, with the birth of their son, they would like to have a bigger place that is part of a wider community more than ever.

Christopher grew up in the East Bay north of Berkeley. However, San Francisco has always been second home for Chris. His parents originally met while living here in San Francisco. Chris spent many weekends and holidays visiting family friends in different neighborhoods, and his summers attending the Academy of Art College's high school program.

Christopher is a designer and artist. He was previously a construction software entrepreneur, and he currently is a cohousing enthusiast on nights and weekends.

John Bela

Urban Design & Neighborhood Placemaking

John is the other co-instigator of this project with Christopher. He has a background in urban design and environmental planning. John spent much of his adult life living in a rental in the Mission. However, when his son was born, he realized he needed more space and wouldn't mind some co-parenting help. This drew him to the idea of living in cohousing.

John moved to San Francisco almost 30 years ago, and after exploring various occupations, he enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley and earned a Masters Degree in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning. John joined the Landscape Architecture firm CMG in 2005, inspired by the practice’s urban focus and the dedication of the founders, Kevin, Chris and Willett to democratic public space design and implementation. While at CMG John designed projects across scales from Mint Plaza to the Treasure Island Redevelopment plan.

Continuing to pursue an interest in art, John formed Rebar with Matthew Passmore and Blaine Merker in 2005. John coined the name Rebar following an inspiring lecture at SFMOMA from the graphic design studio 2x4. Rebar was a loose collective of artists, activists and urbanists before formalizing to become the Rebar Art and Design Studio. Rebar’s first urban project was Park(ing) Day which launched Rebar into the world of urban intervention and opened the door to many opportunities including exhibiting at the Venice Biennale in 2008. In 2009, John left CMG to direct Rebar full time as the practice matured into a boutique art and design studio with a fabrication shop in the Mission District. John led many notable Rebar projects in collaboration with Matthew and Blaine, such as the Panhandle Bandshell, COMMONspace, Bushwaffle, and the San Francisco Victory Garden. As the world was reeling from the economic recession, Rebar pioneered some early examples of interim use on lands left vacant from the economic downturn and coined the term ‘early activation’. Rebar began to dissolve in 2013 as the three founders aspired to pursue their own interests.

While on an artist residency in Copenhagen, John met Helle Soholt, the founder and CEO of Gehl Architects. Following mutual interest in collaboration, John spent a month in Copenhagen as a designer-in-residence. At the end of the month, the plans were hatched for Gehl to expand to the US and join forces with Rebar in San Francisco and Gehl Studio San Francisco was formed. As a partner and director at Gehl, John led a team to help develop the design for the India Basin Masterplan, an urban village in SF that includes 1.5k residential units and approximately 200k sqft of commercial space.

John's current work includes the SF Downtown Public Realm Action Plan with Sitelab, and advising major masterplanning efforts in Baja, California and in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Charles Durrett, AIA

Cohousing Architect

Seminal Thought Leader in Cohousing

Charles Durrett was the first architect from America to visit Denmark over 30 years ago and study how to design and build Danish style bofællesskab neighborhoods. Durrett learned how to facilitate groups of future residents and design cohousing from the best of the best in the world — from both the person who started it, Jan Gudman-Høyer, and the person who perfected it, Àngels Colom as well he studied under Jan Gehl. Years later, things came full circle when many of the current set of leading Danish cohousing architects studied in California under Durrett.

He has designed over 55 communities in North America, including the first bofællesskab style community in Davis, California, in 1989, and has consulted on many more around the world.

He and his team of architects have also designed an equal number of affordable housing projects and schools.

He is an authoritative expert on building these mini-neighborhoods. He has spoken before the United States Congress multiple times. His work has been featured in Time Magazine, The New York Times, The LA Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Architecture, Architectural Record, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, and many more. Charles has also been a guest on a wide variety of televised talk shows, such as The Today Show and a wide variety of other news programs, including CNN, The McNeil Lehr Report, and others.

Charles Durrett has received numerous awards, including the World Habitat Award presented by the United Nations, the Silver Energy Value Housing Award by NAHB, the Mixed Use/Mixed Income Development Award presented jointly by the American Institute of Architects and the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development.

He lives in a 34–unit bofællesskab style community in Nevada City, CA, which he designed with the future residents in 2004.

Michael Yarne

Housing and land use advisor

Michael Yarne, a long time friend of John Bela, is an expert in housing and land use law. Michael’s career spans 25 years of urban development and policy experience, including co-founding a construction tech company, developing over 2,000 units of multifamily, serving in two mayoral administrations, and practicing land use law.

Additionally, he served as an adjunct faculty member at UC Berkeley, teaching a graduate course on land use law and economics.

Learn more at our upcoming event

Sign up for our talk by Charles Durrett (sign up link and date coming soon!)

Further reading

It’s optional, but we highly recommend ordering Charle’s Durrett’s latest book Cohousing Communities: Designing for High-Functioning Neighborhoods.

Contact us

Coho SF